Posts Tagged ‘wellbeing’

Wellbeing Movies

I have in the last few months explored the philosophy of attention-training through the medium of cinema. Attention-training suggests that we can overcome anxiety, boredom, and over-thinking through a focus on the wonder of the present moment. The goal is not distraction but a maintenance of attention, not intensely, but in an open, curious, absorbing way, and on a relatively singular object – the opposite of multi-tasking. Admittedly, cinema is not the most appropriate artform to support attention-training, since movies tend to be given to linear starting and stopping (what I called in my discussion of wellbeing music ‘eventism’), and are usually highly dramatic and full of conflict – this being in the nature of storytelling.

To encourage a mindset in alignment with attention-training, I’ve had to search for films which are not very dramatic, to avoid overstimulation or excitement, but also not too boring, to prevent distraction. At the same time, I’ve tried to find movies which are not overly theoretical or intellectual – attention-training aims to free our non-conscious thinking and feeling functions from interference by our rational ego so movies with complex political or moral subtexts, or straightforward messages are not appropriate. I’ve also tried to get around cinema’s discrete linear stop-starting by locating films without a strong plot, which encourage a less intense meandering or hypnotic quality. Finally, attention-training rejects simplistic polarities, such as good and bad, light and dark, happy and sad, since reality is much more mixed (and these ideas are fictions of the ego anyway). So the tone of these films also needed to be not all sunshine and buttercups, yet still low-key emotional, which excluded a toneless ambiguity – a mood of light fascination was sought.

Anyone following this blog will know of my top 5 attention-training films listed below:

- A Canterbury Tale (1944)

- Summertime (1955)

- Mary Poppins (1964)

- The Railway Children (1970)

- E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

These 5 meet the requirements above plus also seem to reflect the discipline of attention-training in many other ways, which I have discussed in detail in the linked articles.

Interestingly, the process of locating these films also enhances our understanding of attention-training itself through examining additional commonalities between them:

- Going on a visit: All 5 films involve someone paying a visit (to Canterbury, Venice, the Banks family, Yorkshire, and Elliot’s family). The experience of paying a visit aligns with attention-training as visiting inevitably involves viewing the world afresh, in such a way that ordinary day-to-day occurrences become slightly more interesting – I have recently experienced this when my mother came to stay and, even though I was not the visitor, the experience of showing someone around your day-to-day life still encourages this new perspective. The process involves a humble deference, appreciation, and basic compassion toward others which aligns with attention-training. The relative briefness of a ‘visit’ can also be interpreted as a metaphor for our brief visit to life on Earth too, encouraging an appreciation for the mere experience of living. There is also the sense of mild exploration and curiosity about one’s surroundings and the people one meets. This is perhaps the true sense of the saying, ‘Travel broadens the mind’ – and through the mere altered perspective this affords, not necessarily through the acquiring of new languages, interactions with other cultures, how expensive the trip is, or whether you engage in adventure sports.

- The joy of craft: All 5 films feature prominent craft, that is, hobbyist-style or artful examination of objects: the archaelogical artefacts or trades such as that of the wheelwright, blacksmith, or musician in A Canterbury Tale; the beautiful statues and architecture of Venice, and little wind-up toys sold by street-vendors in Summertime; the chalk-painting, busking, and even the matte painting, animation, and animatronic robin in Mary Poppins; the precious period objects and frugal enjoyment of model trains and cakes in The Railway Children; and the fascination of even modern consumer toys and household appliances in E.T. Interest in and practice of craft and pastimes like these are exactly the kind of low-key activities which help with attention-training.

- Characters without a strong sense of purpose: our Canterbury travellers, Jane Hudson, the Banks and Railway children, and Elliott and his siblings – these characters do not have a strong goal or throughline in the narrative of their respective films. They aren’t exactly aimless, but they aren’t, as Mr Banks observes, “fraught with purpose and practicality”. In fact, much of the running time of these films is taken up with characters just hanging out or exploring or enjoying each other’s company. We might similarly reflect that such low-key humble enjoyment is perhaps the best recipe for happiness. This reveals that a sense of meaning is important for wellbeing but having purpose is perhaps not. This aligns with my earlier blog post about the extreme risks of having a specific goal in life, inspirational or otherwise, and of embedding your meaning there; it is as risky as living for a hypothetical future, which increases uncertainty and eclipses your contentment with the present.

Below are some further movie discoveries which perhaps are not quite as specifically aligned with attention-training but share some attention-training elements nonetheless.

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Willy Wonka is super-entertaining and has an unusual balance between light and dark, being a children’s film but with a dark sense of humour, even featuring elements of moral judgement but in a highly warped satirical manner. The key element which aligns with attention-training is its profound sense of wonder in the everyday, expressed most clearly through its central song “Pure Imagination” which suggests that “If you want to view paradise/ Simply look around and view it”. It also savours the everyday through the premise of a world apparently obsessed by a secretive chocolate-maker’s competition to visit his factory. A key element often overlooked is that the plot actually makes very little sense – if Wonka wanted to select a sweet-natured child to take over his factory then the golden ticket competition surely would be the worst way to go about this – yet the magic of the film works all the same (the absurdity neatly weakens the moral messaging and sense of purpose, while appropriately lightening the tone).

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

Hitchcock movies tend to be too dramatic or morbid but this early British thriller has such a playful and adventurous atmosphere, plus it is almost entirely set on a long train journey which provides a kind of hypnotic rhythm that encourages something like a state of distilled flow.

To Have and Have Not (1944)

This is a rip-off of Casablanca (1942) but without its melodramatic doomed romance (and its accompanying histrionic orchestral score). The whole film is filled with a beyond-opposites calm even in the most dramatic World War 2 situations – through the characters’ cynical irony, stoicism, and deadpan humour, as a result it maintains a type of emotional equilibrium not dissimilar than that encouraged by attention-training.

Arrival (2016)

An alien invasion movie that is so understated that it is more a reflection on language and its relation to our perceptions of time, which provides the link to attention-training and our experiences of reality. Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) discovers how language structures time, plus learns how future goals are embedded in the present too. In fact, the alien language functions a lot like a work of art which encodes symbolic gestures of meaning (like music) but outside of linear phrasing (unlike language) – the effect is that the meaning is instantenous (“not conditioned by time”). The film also contrasts the patient present-moment response to a crisis with the histrionic, neurotic response of the overly-ruminating conceptually paranoid military mindset.

Groundhog Day (1993)

A classic of inspirational psychology movies, Phil (Bill Murray) learns to cope with the present moment by reliving the same day over and over until – surprise surprise – he learns to live in the present. Not a film presented in the understated style of attention-training practice, but one certainly with a pertinent message.

Rembrandt (1936)

An understated and reflective biopic of the Dutch artist, basically concerned with various elements of craft and art with a leisurely pace and not much of a plot, reflecting an attention-training-styled mindset.

Rear Window (1954)

So this is another Hitchcock movie, but so unusual for its stationary single-pointed focus on staring out of a window. The dialogue amuses too as L. B. Jefferies (James Stewart) starts noticing a subtle mystery unfolding too, which we could read as a dubious metaphor for the insight gained from present-moment noticing.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s space epic involves an almost-dialogueless experiential space journey which aligns with attention-training’s understated focus and sense of wonder particularly in the style of the film, which is slow and static even as we are blasted beyond the infinite and into the numinous interstellar realms.

The Tree of Life (2011)

Despite being about the grief involved in losing a son in battle, this arty film reflects attention-training through its powerful photography and abstract structure which produces a present-moment experience which combines light and dark, past and present, and ineffable wonder. Its central message is in the importance of cherishing the present expressed through the wonder of childhood.

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Needless to say that Yoda’s philosophy and wise sayings in this film reflect elements of attention-training, but the film as a whole is also a profound work of craft with some of the most detailed and artful sets, costumes, model-work, stop-motion animation, puppetry, and visual effects – particularly if you get your hands on a de-specialised original version (that hasn’t had a lot of this craft replaced by bad CGI). I like to watch a music-only version I made which focusses more on the craft and meaning behind the story rather than the surface plot interactions and sometimes corny dialogue.

The Band Wagon (1953)

This classic Hollywood ‘putting on a show’ musical exhibits lots of great craft of course in its music, dance, sets, and costumes. We can find a hazy connection to attention-training as the plot involves the error of aiming for high-brow alienating ‘art’ (read “concept-bound rational messaging”) over delightful entertainment (read “beyond-opposites craft”), particularly when the final winning show they perform is joyful while making no kind of coherent sense.

A Room With A View (1985)

Again, period films transform the everyday and 19th century upper-middle-class life is understated in a way that aligns with attention-training, as does this film’s storytelling style. The central love triangle plot involves our heroine choosing between a hyper-rational intellectual and an organic connection with a sincere nature- and art-loving young man inspired by love – which we could interpret as representing attention-training if he weren’t a little bit too bombastically Romantic at times.

Ryan’s Daughter (1970)

The period love-triangle in David Lean’s epic romance aligns with attention-training even more since this time our heroine’s choice is between a hyper-sexual but traumatised young soldier and a devoted, wiser, but perhaps rather dull (let’s say, more understated) but genuine older man. Lean’s at times tediously slow-paced direction does certainly pick out beautiful details of the present-moment even in such a poverty-stricken bleak Irish setting.

Life on Earth (TV series, 1979)

Most of David Attenborough’s documentaries are wondrous experiences combining Science, biological/organic knowledge, with lots of present-moment observation of little details. I like this old, first epic series mostly because it has been restored to Blu-ray-quality footage, the science hasn’t been dumbed down for popular audiences, and for its unusually mysterious musical score which belies the cliches of the typical orchestral scores used in his later documentaries.

The Secret Garden

This text is basically aligned with attention-training as it is about spoiled and sick children who become well through appreciating the present moment – the everyday wonders of nature on the Yorkshire moors. I find the novel a little bit too dated and tedious though. The 1993 film looks splendid but the story is cut too harshly so that much of the transformation and its meaning is edited out. My favourite is the 1975 BBC TV series – it looks terrible though (with some nasty cheap sets), so I prefer listening to the audio only for it which I have extracted and basically turned into a radio play.

In the Heat of the Night (1967)

I can’t find any real connection to attention-training except that this crime drama set in a racist Southern US town is creatively photographed by Haskell Wexler, and so patiently directed by Norman Jewison that it has a hypnotic sense of equilibrium. Another “going on a visit” movie, the friendship between Rod Steiger’s rough Southern cop and Sidney Poitier’s patient northern detective is also the quietly touching soul of a murder mystery plot with the temperament for noticing little details, even while the final denouement always seems a little confusingly executed (although I argue this just enhances the atmosphere as something to savour in itself since the plot quietly disappoints).

The Winslow Boy (1999)

A textbook example on how to translate a play to film, and another period movie, The Winslow Boy exemplifies attention-training through its consistently understated style with observation of little visual details throughout, reflecting Edwardian sensibilities but also in its preoccupation with avoiding melodrama while it is itself a melodrama. It is essentially a court-case movie but with all the courtroom scenes removed (Rattigan performed a similar trick in The Way To The Stars, a movie about WW2 fighter pilots which doesn’t include any scenes set inside aircraft). Instead we focus on the family home and impacts on the middle-class family. Its quiet preoccupation with the present moment is also revealed through its questioning of the central plot’s pursuit of justice as righteous but perhaps ultimately costly and unnecessary.

Wallace and Gromit trilogy (1989-1995)

Claymation involves an obvious craft element and Nick Park’s original trilogy of Wallace and Gromit half-hour films A Grand Day Out, The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave combine humour, a surprising sense of drama, and quiet originality. There is also a homely sense of modest joys – of simple word play, visual storytelling, homemade inventions, and the enjoyment of cheese and crackers, toast with jam, and reading the paper. Surprisingly, the most aligned with attention-training is actually the more humble A Grand Day Out, usually considered the more primitive prelude to the impressive plot-laden sequels, which have their moments but also generally tend more toward the distraction of entertainment (unfortunately, going too far in 2005’s less original, more cliche-ridden A Matter of Loaf and Death which I don’t recommend).

Where do YOU put your attention?

It has taken me some time to realise that this is the ultimate ‘quality of life’ question we rarely attend to.

1. Attention-Training

Why is attention so important?

What sets humans apart from animals is our capacity to think reflexively; we can use metaphor to construct hypotheticals, to problem-solve, to imagine, to anticipate and to plan.1 This means that, unlike animals, we have far more control over how we think – where we place our attention: on what we are doing, on what happened in the past, on planning for the future, and on abstract or imagined concepts that are not currently happening in front of us. However, this unique ability to ruminate also makes us exceptionally prone to anxiety, boredom, and intellectual confusion as we constantly visualise potential dangers, become muddled in abstract concepts, and invent elaborate fantasies by which we judge reality and find it wanting.

What’s the solution?

The Buddhists call it ‘stilling the mind’. If the mind is pictured as a ceaselessly churning lake, ripples emanating from and spreading in all directions, we should seek to calm the stresses of mental agitation, and, in so doing, allow the surface to reflect a clearer perception of reality. The method, today usually called ‘Mindfulness meditation’, is apparently straightforward: take time-out to sit comfortably and focus your mind on your breathing or on the senses: your hearing, sense of smell, or the sensations of the body at rest. The goal is to focus on the present moment only, or simply observe non-judgmentally the thoughts that come and go. This trains our attention toward less cluttered, chaotic, and unrealistic thinking.

Why is this helpful?

Merely relaxing, being distracted, blanking out or ‘escaping the world’ isn’t the goal – meditation is clearly differentiated from sleeping, which is one of the reasons why a relaxed but straight-backed attentive upright posture is usually suggested. The goal is not distraction but a maintenance of attention, not intensely, but in an open, curious, absorbing way, and on a relatively singular object – the opposite of multi-tasking. Our focus should not be too exciting because this will lead to anxiety or over-thinking. However, just staring at a brick wall is too unexciting for the average person (inviting distraction) – our minds do need some stimulus. Our breathing is therefore a good focus because it is decidedly not exciting, but does retain basic ongoing motion. Breathing is a great ‘back-up’ focus too as it is always available to us in any situation.2

I don’t like focussing on my breathing – what else can we do?

Anything similarly offering or encouraging single-pointed focus with reduced conceptual stimulation. Most ‘chores’ provide this: washing the dishes, sorting the washing; and the more minimalist leisure activities: doing a crossword, completing a jigsaw puzzle. This is providing you approach them with a suitable mindset: focus on the task itself, but don’t rush; avoid rumination on related or unrelated topics; retain attention against drowsiness. Focussing on the task itself implies a patient moderate pace because rushing is usually caused by aiming to get the task over-and-done-with as quickly as possible – implying a focus on the future instead of the present. In fact, a type of steady rhythm is implied.3

2. The Present Moment

Why focus on the present moment?

The present moment is living – it is all living consists of. The past and the future are purely concepts probably unique to the human mind. While squirrels gather nuts for the winter, it is doubtful that animals can conceptualise the past or the future (they have conditioned behavioural responses rather than understanding). While reminiscing and forward-planning have their uses, modern humans tend to ruminate around these excessively, undermining our experience of living. A focus on the present moment is calming, as we are not cluttering up our thinking, and it encourages effective flexibility and adaptation: it helps us to become more open to input from elsewhere, both the world around us and our unconscious inner workings too.

Wouldn’t this be easier if we trained our focus on something more interesting?

This is actually the usual less effective solution to our existential discontent: when we are stressed or over-thinking, we distract ourselves with amusements. Entertainment provides us with a contented feeling of engagement – but only while it lasts. And we can’t be entertained all the time; even if we didn’t have to attend to other things (work, meals, etc.), most amusements grow stale after a while and we need to keep searching for novelty. So instead of trying vainly to fill our lives with constant amusement, which is really constant distraction, we can learn to focus our thoughts on whatever happens to occur, essentially finding the mere experience of being alive engaging, while developing a centring adaptability to circumstances.

Should boredom be addressed differently from anxiety?

Boredom often results from too much conceptualisation: instead of attending to each moment as a unique event occurring around you, you instead dismiss, overlook – essentially stereotype and pigeonhole – much of what occurs. You simplify the complexity of reality into bland categories – of the past: you’ve “seen that, done that”; or of the future: “nothing interesting will ever occur from that direction”; or into a simplified abstract description: “this is a typical (and tiresome) everyday instance of this”. A common modern source of boredom is utilitarian emptiness: living your life for some future materialist goal such as a paycheck or holiday. The abstract distortion here is seeing everything as merely a means to that end: “the daily grind”. Anxiety is more concerned with rapid neurotic thoughts, ruminating on myriad conceptual scenarios in the past, present and the abstract, yet both boredom and anxiety have the same solution: slow down, attend, notice what makes each moment unique, stay in the present.

How do you ‘focus on the present moment’?

Focussing on the present involves more than simply not focussing on the past or the future, and not conceptualising. (Being bored is also not being present.) You can really only focus on the present by being interested in it. The Buddhists suggest mild counting – count your breaths up to 10 then start again at 1.4 Or choose a focus on your senses – what can you hear? What do you smell? Observe. Notice patterns. Notice movements. Notice colours. But don’t think about them, e.g. noticing the colour green is very different from considering whether you like green, or what associations it has – this is rumination (taking you away from the present moment), not noticing. Personally, I find noticing light fascinating, or detecting aesthetic or organic patterns around me.

3. Emotion and Attention

What about contemplation?

Contemplation involves choosing an image or idea to meditate on. Traditionally, the image would be something calm and centring, such as a relaxing beach scene or the image of a god. However, a contemplative image is, I fear, too conceptual. The idea of overcoming excessively conceptual thought with use of a concept seems hazardous. A contemplative image can also be too stimulating. Meditating on chocolate cake or someone sexy is really just fantasising; like pursuing constant entertainment, this is more about distraction than training your attention. Sometimes mild distraction is helpful in times of stress, but this is not attention-training. The problem with contemplation is that it isn’t about attending to the present moment, and generally it is too emotionally involved.

Shouldn’t there be some emotional involvement?

Emotion can distract and overpower. Just as staring at a brick wall would be too under-stimulating to attend to, overstimulation is too challenging to train your attention as it scatters attention in a way that is difficult to control, at least to start with. Present moment excitement also leads to dizzying highs of anxious excitement followed by disappointing lows when the stimulating event is over, producing a bipolar roller-coaster effect. The real problem of hyper-stimulating events being unsustainable isn’t about how to find means of sustaining them but more about reining in this hedonic treadmill – initially we want to adjust the amplitude of the curve and keep our highs and lows to mere slight variations in a stable, relatively constant level of stimulation, at a more sustainable level of contentment, where we can maintain single-pointed attention and responsiveness. Super-stimulating events are therefore skipping to an overly advanced level of attention-training, likely to disrupt and undo your progress.

But surely we shouldn’t be unemotional robots either?

True. Emotion is, for living creatures, largely unavoidable. In fact, a small or moderate amount of emotion can aid attention. Bhakti yoga suggests fixing the mind on an object you greatly love – if God is not enough, focus on your son or your favourite pet.5 Again, this sounds dangerously distracting to me, but maybe there is some benefit of slight-to-moderate emotional involvement – and in the present moment rather than in your imagination. Instead of merely noticing or observing in the present moment, what if we let ourselves be fascinated by, find wonder in, or love the colours, the movement, the play of light, the smell or sounds? I can’t think of any objections here – provided we stay in the present, with a low-key focal point, and don’t allow our excitement to rush off into anticipation, remembrances, or associations. Importantly, calmness does not mean unemotional lack of concern: it means the ability to appreciate reality (love life) rather than ignoring or distorting it to suit our own ends.

4. Utilising Attention For Enhanced Performance

How is attention-training useful for performing well in intense or stressful activities?

Attention-training is important for everyday contentment but it also provides us with a clearer head to respond effectively in important life situations, situations we may or may not have prepared for but which require unpredictable adaptive performance to succeed. These situations invite high levels of anxiety as our minds furiously try to second-guess the best responses and rush off into distracting hypotheticals such as worst-case scenarios. We can overcome this by focussing our attention effectively. The key is to find something not overly emotional in the present situation to notice or be fascinated by.6 ‘Notice’ is crucial – not ‘stare at intensely’ or ‘manipulate’ or ‘theorise about’. It should be in the present situation because otherwise you are not attending, you will be distracted away from rather than responding to the moment. For most activities with a clear goal, the focus should be on a factor which changes in relation to that goal, e.g. “Keep your eye on the ball.”7 For most activities involving other people, your focus should be on the other person’s present-moment responses.8 The key is to ‘notice’ rather than ‘plan, build contingencies or pass judgement’.

Surely these more high-intensity activities should involve more not less complex thought and planning?

Animals don’t plan; they respond. Yes, this is why they aren’t great at architecture or quantum mechanics, but animals are also quick learners, skilful responders, and confident performers, as indeed are infant humans in ways that often put adults to shame.9 The human capacity for complex thought is generally overused – on a daily basis few of us actually need to undertake reflective analysis, run probability hazard assessments, or use advanced calculus (and we doubtless should not be doing these under stressful circumstances anyway). Most of our abstract ‘reasoning’ often gets in the way of our ‘animal’ instincts – our inbuilt organic aptitudes for physical movement, physiological processing (such as breathing or digesting our food), non-conscious mental processing, and our emotional needs. Often the best thing our ‘genius’ human thinking capacities should do is to get out of the way of our bodies.10

Why is the body so important?

The distinction between mind and body is one of those abstract fictions of human reasoning.11 Your body including your mind has involuntary highly complex mechanisms that your rational thinking capacity literally cannot understand or mimic effectively. The motion of a falling tennis ball requires complex mathematics that is impossible to consciously ‘calculate’ in time to catch the ball – but we can of course train to do this consistently and easily. We underestimate the huge degree that our mental functions are similarly capable without our conscious involvement: I need only mention language use, facial recognition, fully-automated skills such as well-learned multiplication tables or social skills – these mental abilities develop either entirely without our noticing or much more effectively if, like infants, we don’t ‘think’ about ‘trying’ to ‘learn’ them. The importance of living through the whole organism is reflected in the focus on sensory awareness during Mindfulness meditation too. We need to stop thinking so much.

But shouldn’t difficult situations require us to try harder?

One of the big revelations associated with attention-training is the radical redefinition of what we call ‘effort’. Effort is not about ‘trying’. ‘Trying’ is mentally forcing a goal with all your ‘rational’ might.12 This is not how animals act. The human ‘trying’ is a narrow, tunnel-vision straining, executed in the spirit of a despotic command or superstitious wish-fulfilment. In ‘forcing’ an objective, we often fail because we waste energy tensing muscles we don’t need to use and over-thinking unnecessary anxious contingencies: harbouring neurotic doubts, nursing convoluted ‘theories’ and ‘tricks’ we desperately ‘try’ to remember – or we ‘give up’ and adopt a bored nihilistic fatalism which is just as distracting.13 We thereby miss valuable guiding possibilities in our present-moment surroundings, and we close off help from our broader organic reactive mechanisms.

5. Adaptive Learning

So how do we ‘try’ then? How can we learn and achieve?

The Buddhists call it “effortless effort”: to learn something, don’t ‘try’ instead notice.14 Notice the key facts, related concepts, or actions required for the task. Visualise (rather than itemise) or notice examples, then practice with awareness of cause and effect, with interest but without judgement (which is one of the most harmful forms of rumination). Allow the organism to react by focussing your attention on relevant, observable, and interesting details of the present moment – do not ‘try’ or ‘help’ your mind or body to ‘improve’; avoid forming ‘theories’ about the learning process, observe accurately and allow the organism (mind and/or body) to respond. Progress with curiosity, fascination and surprise, not encouragement, worry or judgement. Act like infants, who learn without rumination or correction, or like a seed: the growing plant does not require instruction, judgement or encouragement, only occasional support, pruning (removal of unnecessary encumbrances) and patience to unfold organically.15 The most effective learning happens when we don’t notice, actually when we have little to do with it.

Are you suggesting we learn better when we don’t care?

No. If we didn’t care, we would prevent the organism from noticing and building response patterns effectively. What I mean is that your rational, practical ego, that ‘you’ that thinks it is in charge, needs to step back and allow the organism to act with its superior abilities. The key word is “let”.16 Let the organism grow. If you know how, let it happen. If you don’t know how, let it learn.17 The metaphor here is ‘submission to God’;18 sacrifice, crucifixion is the role for your interfering ego. It really is as if your organism is an entity that isn’t you; your organism is an unknowable, self-acting force that performs through, around or with you. “The fates lead him who will, him who won’t they drag.”19 Half the people are ‘trying’ every day and frustrated. Others are giving up and being ‘dragged’, blown with the wind, aimless and defeated. Reality is between the opposites; our ego needs to cooperate, not dictate or abdicate.

How can I cooperate better with my organism?

By supplying the organism with everything it needs to learn, while getting out of its way. But the hardest thing about this is that we are terrible at acting on negative goals – “to not interfere”: it is as easy as obeying the instruction not to think of an elephant: we instantly do. The more we fight against our ego the larger it looms in our awareness and the stronger it becomes. Instead, we need a positive goal, something we can actively do, but which doesn’t interfere. This is why we observe and notice key variables instead. As above, I think we can enhance this by aiming beyond noticing to fascination. We can also aim beyond practicing by transforming it into playing. Playing involves a trial-and-error focus while acting with curiosity and joy, rather than judgement or criticism.20 An observable, interesting variable relevant to our task is not just observed but played with, varied, repeated, broken apart and reassembled for the joy of it, allowing the organism to learn on its own, in the most effective way.

Is this like treating everything as a game?

I would go so far as to say that viewing learning as a game is the most effective way to learn and achieve – provided we are discussing a playful experimental game, rather than a zero-sum unforgiving mechanistic competition. This is so effective because a playful game situation is a perfect trial-and-error response-training situation. A playful game is basically a simulation of reality where there are no real-life consequences (such as incurring injury or loss from making mistakes) but actual real-life organism responses are trained, that is, the points you earn or lose are meaningless but you do actually gain real skills at playing that game, exercising your decision-making processes, and expanding your emotional experience along the way. A game, correctly played as a game, is fun, provided it is played for its present-moment enjoyment, not in order to win money or status or fame or for any other ego-centred or overly-conceptual goal.

6. Ego-Distractions: Distortions of Reality

What is wrong with playing for ego-centred goals?

Ego-centred goals are the ultimate distraction from effective performance. As if this were not enough, they are founded on a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of reality. The ego, your rational sense of ‘you’, thinks it controls all of you, mind and body included. It thinks it deserves credit for any success; it values power, fame and notoriety; it seeks to transform the ineffable experience of living into some kind of material prize. To convince itself of this untruth, it views the world with only one eye open, ignoring all the evidence of its relative impotence, splitting the world into opposites: mine and yours, good and bad, black and white. Its desires consequently beget fears, leading to debilitating self-doubt, fears of failure, lack of control, and uncertainty. All of this comes from a huge misconception: chance, the performance of your opponent(s) and your own reflexes are not effectively under your control, hence, in seeking glory for itself, the ego strives vainly for the impossible. In fact, the ego itself is a generalised concept, a fiction of the mind trying impossibly to look back on itself, and acting from this false centre is at best limiting, at worst destructive.

So is it wrong to succeed or earn money with a job?

There is nothing wrong with gaining money or status or fame from success, but making such gains your goal is a huge distraction from performing well and finding contentment. This is because such gains are ends (desired results, end-goals), hence they are fictional concepts about the future. Attention-training reveals that we need to radically re-define what we mean by ‘goal’. A ‘goal’ can be deceptive and lead to anxiety because it is usually concerned with the future and is often highly conceptual. Winning is a future state – and the future doesn’t exist: it is a distraction from your present game. Instead of attending to the reality of the situation, your mind scrambles into the future, wishing, willing yourself to win at all costs, dreading in elaborate detail the consequences of losing, or fantasising around the glory of your triumph. In that moment, distraction occurs, and you miss a key detail needed to respond successfully to your present situation, or, worse still, you are motivated to ‘try’ and use your rational mind to interfere with your organic responses which are actually superior. Also, as we mentioned earlier, prolonged focus on the future results in the transformation of reality into a dull or anxious world as a result of not attending to the glory of the present.

So we shouldn’t have goals then?

Yes and no. Humans excel at problem-solving because we are able to envisage conceptual goals. However, these types of goals are actually just the theoretical idea of a consequence or endpoint; we need to convert these ideas into practical goals if we want to act on them. What I am calling ‘practical goals’ are either really straightforward (e.g. “Open the window”) or, more importantly, take adaptability in the present moment into account (such as “Keep your eye on the ball”). To be adaptable is to respond to situations as they arise. This requires flexibility and improvisation – which is achieved by ensuring the goal refers to the present moment, and is always capable of being done in your situation. “To win the game” refers to a future state and can’t always be actioned, while “to notice the ball” is present-moment and always actionable. Not only can you always “notice the ball”, but you allow your organic processes (which are not entirely under your control) to respond with maximum adaptability because you are supplying them with the up-to-date information they need, and you are not distracting or interfering with them.

Does this mean we shouldn’t try to win?

Giving up and deciding you’re not going to win is as unhelpful as deluding yourself that you will win. Just as some people become frustrated and give up playing when they make too many mistakes, others actually quit when they are becoming successful: their ego butts in screaming, “Hey, I’m actually going to win this! I’m better than everyone!” and distracts their game.21 This seems to imply we should be aimless and non-committal, but more accurately we should really be adaptable. We need to be open to winning – being open is part of being responsive, and part of being responsive is to focus your attention and allow the organism to respond. So we shouldn’t ‘try’ to win, or, put another way, we should always try to win but ensure we go about this the successful way – by engaging the whole organism in the present, rather than just the impotent ego in some hypothetical fiction about the future.

7. What you can and can’t control

Surely you are not suggesting that we need to just focus and we will always succeed?

No. Attending and responding will only allow us to perform at our current capacity. And there are many elements of any situation that are out of our control: everything from our genetic dispositions to certain personality propensities as well as chance. But training our attention puts ourselves in a position where our bodies and minds can perform, or learn and improve as efficiently as possible. For learning, a trial-and-error situation, best viewed as a game situation, is essential but our progress also depends on the quality of our past experience too. For example, you don’t learn by playing against an opponent that is less skilled than you (as they teach you nothing new) or far more skilled than you (as their superior skill will seem like mysterious magic).22 You learn most effectively by playing against an opponent who is about one level more skilled than you, then playing at your best capacity. Importantly, you don’t even need to win or succeed to learn effectively from this situation – just focus and allow your body and mind to attack the problem.

How can I stop feeling so bad when I lose a game or fail at a task?

By realising that ‘you’ are not in control. The polarised concepts of “success” and “failure” come from the ego thinking it controls everything. As we discussed above, winning or losing has almost nothing to do with you, your ego, since all you need to do is attend to the game and let the organism do the rest. Winning or losing is only meaningful in relation to attention-training, not the game or situation itself. If you won but your ego was interfering (i.e. you were anxious and desperate), you actually didn’t win – you haven’t improved your attention-training; your opponent probably just slipped up, was too weak, or you got lucky. If you lose but didn’t waver in your attention, you actually won – in that you have improved your attention-training; your opponent may be too strong for you currently, or was lucky (or you need more training, hence there was nothing further you could do for the moment).

But surely we cannot learn without some judgement of right or wrong, win or loss?

There is dangerous confusion here between judgement and outcome. Judgement involves applying polarised concepts to the external world or, worse, yourself. An outcome is just the consequence of a cause, the result of a particular act. If you knock over your drink bottle and water spills everywhere, the judgement might be “I’m such a klutz” but the outcome is just spilled water. Outcomes are valuable learning tools as they constitute feedback, allowing us to adjust our behaviour in future. But judgement spreads inaccurate polarised conceptual thinking: you think “I am a klutz”, therefore there is now a non-conscious propensity to keep acting clumsily to prove your judgement correct, or to ‘try’ not to act in this way to save your hurt feelings. We need to notice outcomes accurately, in high fidelity, to learn – if you didn’t know you had knocked the drink bottle over, you would not learn to avoid this in future – but the key is to ‘notice’, not ‘judge’, and the two can be difficult to distinguish, hence the importance of attentive focus on the present, avoiding unnecessary conceptualisation. Ultimately judgements are human fictions – there simply is no measure that can ultimately judge a human being.

Since we shouldn’t ‘blame’ ourselves for mistakes, does this mean that we shouldn’t ‘celebrate’ successes?

Surprisingly, yes. Celebrating success and wallowing in failure are two sides of the same coin as both strengthen the concept of the interfering ego (“I’m good/bad because of my success/failure.”). Celebrating success is dangerously similar to encouragement, which advocates ‘trying’ to continue the success (or avoid failure), thus splitting the world into simplistic opposites again, setting us on the path to distraction and anxiety. Encouragement is applied under the mistaken belief that the student might give up due to experiencing failure, but both encouragement and failure inspire polarised unrealistic thinking, as do social comparison and external rewards, physical or psychological.23 Instead of celebrating victory, we should instead celebrate our enjoyment of the game (the present-moment playing of it), whatever the outcome. I’m not advocating “participation awards” here – since these are still judgemental material prizes in their way – but really experiencing a satisfaction in the present-moment performance is the most beneficial attitude to have here.

How can we encourage more openness and learning?

By encouraging patient low-key attentiveness towards and enjoyment of the present-moment task and playful practice. A great teacher or leader does not issue threats or praise, corrections or encouragement (which involve polarised judgements) but draws the student’s attention to a newly relevant factor (derived from recent outcomes) to notice in detail. The teacher might suggest the student should “notice”, “contrast”, “compare”, “consider”, “be aware of”, “explore”, or “experiment with” those factors rather than giving direction as to specifically how the teacher ‘thinks’ that factor ‘should’ be adjusted.24 Outcomes are then reviewed and the process can be repeated (to build practice) or the focus adjusted again. The student need only focus on a key factor and notice it, realistically ‘measure’ it, without trying to ‘correct’ it or resisting any organic change that might occur as a result: invent nothing and deny nothing25 – just notice and allow a response to form.

How can I be proud of achievements when I don’t feel as if I did them?

It is true that attention-training can lead to improvements in performance that can seem magical, even unexciting, as if ‘you’ didn’t really do them.26 Some people find this disconcerting and would prefer to ‘force’ victories by ‘trying’, but I suspect a ‘forced’ success is more luck than achievement, or, at worst, the achievement is undermined by the harm done to yourself or others in the process: this is very much an end defining the means. However, feeling surprised and somehow not responsible for certain successes is actually a brilliant triumph – not over adversity so much as against your own capacity for distracted over-thinking, boredom, and anxiety. In a highly competitive environment, this is an astounding achievement of mindful practice and self-possession. The capacity to simply attend in the face of the often ego-centred distortions of competition or other extreme stresses is true heroism; the power to resist overthinking, egotism, self-blame, and ‘trying’ interference is the true meaning of faith. Thereby is self-actualisation truly a side-effect of self-transcendence.27

8. Exceptions or moral qualms?

I can understand this is a great philosophy for learning physical performance skills such as sports or music, but does this really apply to learning abstract conceptual topics such as mathematics, literature or sociology?

Skills which produce clear, objective, and immediate outcomes – winning or losing a volley in a tennis match, solving a maths equation, etc. – are easier to learn because the feedback is clearer and more reliable. But all skills can be learned in this way, even such highly conceptual and idiosyncratic skills as winning political office, pleasing an art critic, or finding a romantic partner. Skills in these areas can be more difficult because outcomes are even less in our control. The relevant factors upon which we must place our attention can include the more or less contradictory opinions and beliefs of various social groups, the fickle fashions of aesthetic criticism, even the accidental coincidence of personal tastes. However, the principles are the same – there is still no benefit of overthinking convoluted schemes to somehow circumvent circumstance: we can only train the organism and attend, while practicing lots, and resisting ‘trying’, remaining aware of what we can control and what we can’t.

How about learning in a ‘rigged’ situation, such as someone facing systematic prejudice, political corruption, or a fixed sporting match?

These are all circumstances beyond our control, or irrelevant to attention-training. If you perform the best in a sporting tournament, but the gold medal goes to the runner-up who had better political connections, nicer hair, or an umpire made an error, this says nothing about your performance, only about the misjudgements of others. If you are frustrated by this prejudice, you might like to change your conceptual goal from winning at sport to combating prejudice in our society, but you can still approach this new conceptual goal in the same way, by attending to the causes and effects of prejudice and playfully exploring the viable avenues for implementing realistic change. Attention-training has a realism which should help you recognise when you are striving for a goal you can’t achieve due to circumstances or simply because such a goal isn’t actually what you, both mind and body, ultimately want. Sometimes giving up is a relief based on realism, and a win for our wellbeing.

Could you use this performance-training method for corrupt, egotistical ends?

I suppose you could keep calm in the crisis of the hideous murder you are about to commit by using attention-training – presumably this is what soldiers do in combat: build combat skills, attend through reconnaissance, then act with present-moment attention; indeed, much of the Zen background of attention-training is associated with samurai tradition. The morality of such situations are human concepts really, but there are some reassurances: attention-training properly encourages a thorough examination of reality – hopefully such examination will expose corrupt intentions behind a given project. Furthermore, egotistical actors are more likely to use egotistical means to achieve their ends so are unlikely to have the patience and self-possession for attention-training. Also, as discussed above, attention-training cannot guarantee a particular outcome because its very modus operandi is that we are, egotistically, largely powerless in the face of chance, the organism and other complications of circumstance. There is also a fundamental unrealistic contradiction at the heart of egotistical acts – egotistical success is hollow: the resulting fear, paranoia, boredom, and disturbing fictions of the clashing opposites will turn all seeming-success to dust.

Is there a morality to attention-training?

Moral concepts are largely fictional human concepts that are contingent, that is, they depend on situation and perspective. But I think there is a universal morality in terms of what is healthy for human thinking: anxiety, boredom, and intellectual confusion are not healthy states of mind. Attention-training suggests the extreme egotistical corruption of various societal evils. For instance, the attraction of slot-machines is pure egotism since there is no thrill without the desire for winning, yet there is nothing you can actually do to better the odds of winning – in a game of pure chance, there is nothing to learn except for the emptiness of the exercise: slot-machines are a trap for humanity’s egotistical wish-fulfilment fantasies. However, the adaptability engendered by attention-training suggests that even in situations of apparent egotistical corruption, there are possible compensations – through shifting the rules of the game you are playing: for instance, if the slot-machines were part of some more meaningful, skilful social interaction perhaps. It’s just that this seems unlikely and incidental.

What else would attention-training condemn?

All forms of unrealistic thinking: the suggestion that we can achieve or be happier through mere wish-fulfilment, “believing in yourself”, ‘forcing’ ourselves or others to our egotistical will, treating the world as an instrumental means to an end, living in a fantasy-land of over-interpreted political, social or religious concepts. Leisure activities that don’t encourage low-key single-pointed focus with reduced conceptual stimulation and/or a sense of wonder at existence would be considered merely distraction – although distraction has its purposes too as a kind of stopgap against depression and anxiety (and, of course, achieving other more material, practical goals). Attention-training otherwise doesn’t have much to say about which activity you choose to pursue, which game to play; this can safely be left to conceptual thought, as long as it is not played egotistically and is enacted with attention and openness in the present. The most basic takeaway of attention-training is the ineffable wonder of living, of beholding the world around you, wherever you are. People placed in horrendous and desperate circumstances can still attend to this, though it may be immensely difficult when basic needs are not met. This ineffable experience-reality is the basic argument against egotistical acts, anxiety and despair – all corrupt human conceptualizations should properly pale in comparison to the wonder of living which need only be noticed.

9. A reliable centre of stability

What are we really doing when we focus on the present moment?

We are actually becoming more fully aware of the wonder and mystery of consciousness itself28 – that is, our ability to perceive, which is, again, all our lives consist of. Scientists theorise that our perception results from something that occurs in our bodies or brains but the exact mechanism, how it comes about, and what it actually consists of is not known. Furthermore, present-moment consciousness is all you consist of – because your past and your personality are only ever concepts, ideas or approximate generalisations. These concepts frequently cause anxiety or limitation, but by focussing on the present moment, on consciousness itself (and our identity with this), we can gain insight into the truth: that consciousness is actually undefinable, irreducible and mysterious, and so too are our lives, when fully realised.

How is the mysterious nature of consciousness comforting rather than disorienting or frustrating?

Consciousness is mysterious and ineffable but, provided we are practising attention-training, it isn’t random or unpredictable – in fact, it is the single most reliable support for our lives. It is a disorientating fact that nothing else in life is truly dependable, mainly because everything is necessarily in a constant state of change: the weather, the economy, social customs, families etc. – the universe is always changing, and all living things must die. Many of us find comfort in seeking a foundation or support to turn to in times of strife, a kind of home or centre, such as a romantic partner, a church, or a physical home – but the disturbing reality is that all of these are unstable too. Consciousness however is truly stable – your perception is always with you: because it is you. Through an awareness of consciousness, you discover a truly reliable ‘psychological’ centre that can’t be taken from you.

But surely our consciousness is also unreliable as we all will die one day too?

It is true that we will all die one day, so our consciousness will, theoretically, end. However, we are consciousness, so when consciousness dies we will not be around to notice. In other words, you can’t be conscious of your own death except as a theoretical concept before it occurs. In this sense, consciousness actually is infinite and eternal – you will certainly die, but you can’t ‘be’ dead, or ‘know’ you are dead by definition. Hence being dead is just like not being born yet – a state of existence no one can experience. Attention-training suggests that death is much like falling asleep, merely losing consciousness. Most of our fears surrounding death have to do with conceptualisation – we think about the end of our Unique Personalities, of our Achievements or Positive Experiences – and about our miserable experience when we will never meet our loved ones again. But, once more, these are all just ideas; we will never experience the loss of these concepts because when we are gone we will not have any experiences – including experiences of loss or loneliness or regret or joy or anything.

If death still happens, but we just can’t think about it, isn’t this mostly denial – simply avoiding unpleasant thoughts?

Avoiding unpleasant thoughts is good for you – it is only considered denial or avoidance when such unpleasant thoughts are necessary for some important purpose, or when a deception is involved. If I avoid thinking that, say, my partner has left me, this isn’t denial provided there are no consequences of our relationship that I am relying on, such as companionship or shared child custody or a mortgage etc. Often denial isn’t simply not thinking about something important, it is actually thinking the opposite of something accurate – I’m not just not thinking my partner has left, I’m actually thinking that they are still with me: that is true denial. However, avoiding thinking about never seeing my loved ones again because I will be dead isn’t denial because I am not suggesting replacing this thought with the delusion that I will see everyone again in a mythical afterlife (which there is no evidence for). The thought should be put out of your mind because it is simply invalid – it is a miserable thought about an occurrence that it is impossible you will experience. It is basically a complete fiction, in the same category as ‘wishing’ or ‘trying’ to believe something false.

If it isn’t denial, you seem to be advocating avoidance of a lot of significant concepts humans live with: the ego, death, personal history, goal-setting, encouragement, etc.

Ironically, attention-training could actually be summarised as “avoiding unpleasant thoughts” – directing our attention in a healthier direction away from the echo-chambers, circular thinking, concretised concepts, and superstitions of our uniquely human reflexive thinking with which we started this discussion. I am not trying to suggest we can completely free ourselves from these concepts, but one of the effects of a greater awareness of the wonder of consciousness is that everything else rightly pales in importance. The more we experience living, the safer it is to interact with psychologically problematic concepts such as the ego, death, polarities like success or failure, or conceptual goals – because we can then view them with a sense of perspective, essentially as the incomplete, mostly fictional, relative (not absolute), temporary, and approximate concepts which they truly are: they are tricks of our mind which we can use sometimes to our benefit, but often to our detriment. When these ideas are taken too seriously, they are destructive and simplistic, they make the world appear like a struggle for survival (a ‘survival of the fittest’ or a dour realism movie), and if we are unable to see them playfully, we would do well to avoid them, in the same way we enjoy the sunshine but avoid staring at the sun.

Conclusions

Can you summarise these ideas?

Humans are great at conceptual, reflexive thinking but this also makes us vulnerable to heightened anxiety, boredom and intellectual confusion.

We can mitigate this by learning to maintain attention around a singular focal-point, which not only frees up our superior non-conscious organic response mechanisms but allows us to view the world more realistically in the present moment, defeating the neurotic fictions of the ego and its over-inflated sense of control.

Whether you want to learn or perform at your best (your current capacity) or generally want to increase contentment and joy of living, attention-training encourages adaptability and flexibility by suggesting we should:

- Find something not too exciting and not too boring to focus on in the present moment which is relevant to our task, observable and basically interesting/fascinating

- Give your organism enough material (relevant facts, concepts, or actions, in detail, preferably at not too easy or difficult levels of complexity) for it to practice on (learn from) in a playful game-like way, and then

- Attend openly, playfully, with wonder at the glory of living.

Most goals are actually theoretical ideas about consequences, not appropriate actions for performance. ‘Practical goals’ are focussed on the present moment and should be always actionable in the specific circumstances.

Effort isn’t straining to do the improbable, wishing or ‘trying’: it is having the patience to notice the right things in the right way and having the faith to step back and let it happen. Achieving this or not in a particular moment is the only true measure of success.

Winning and losing, success or failure, are largely out of our direct control (and are often measured by unrealistic egotistical and/or conceptual standards anyway). We should be open to all outcomes, notice them, but avoid judgement on the basis of them, then play the game which seems most appropriate for who we are in the circumstances in which we live with our focus on the enjoyment of playing itself.

Present-moment consciousness is all you consist of – awareness and wonder of this is, in terms of wellbeing, primary; all other concepts are rightly secondary in importance as they are illusions of thinking which are only occasionally of benefit to us.

References

1. Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens. Harper, 2015.

2. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

3. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

4. Khema, Ayya. When the Iron Eagle Flies: Buddhism for the West. Wisdom, 2000.

5. cf. The Bhahavad Gita, in many editions. See my earlier post about the Gita here.

6. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

7. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

8. Bruder, Melissa, et al. A Practical Handbook for the Actor. Vintage, 1986.

9. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

10. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

11. Damasio, A. The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Vintage, 2000.

12. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

13. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

14. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

15. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

16. Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Tennis. Bantam, 1974.

17. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

18. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

19. Campbell Joseph, Moyers, Bill. The Power of Myth. Anchor, 2011. Also attributed to Seneca.

20. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

21. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

22. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

23. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

24. Green, Barry & Gallwey, W. Timothy. The Inner Game of Music. Anchor, 1986.

25. Mamet, David. True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor. Vintage, 1997.

26. Gallwey, W. Timothy. Inner Tennis: Playing the game. Random House, 1976.

27. Frankl, Victor E. Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon, 1962.

28. Tolle, Eckhart. A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose. Viking Press, 2005.

Wellbeing music

Beethoven’s famous 9th symphony can be seen as a search for the best music:

1st movement: expectant, noble, bold.

2nd movement: boisterous, terse, briskly grand.

3rd movement: reflective, pastoral, profound.

4th movement: Beethoven quotes themes from the earlier movements each followed by a blast of disapproval and grumpy passages in the lower strings which imply disgruntled verbal rumination: “No,” he seems to say, “I liked that music for a time, but it’s not ultimately satisfying.” Those lower strings then find Beethoven’s famous “Ode to Joy” theme, but even this is dismissed and abruptly the symphonic orchestra gives way to the human voice – of the singers and choir with this new theme, and then the orchestra, vocalists and choir take on the most rousing ‘feel-good’ ending in the Western Classical repertoire. So apparently Beethoven likes this better.

I mention Beethoven’s 9th’s testy musical ruminations as I have been undertaking something similar in the last few months. My new, more relaxed job leaves me time for reading, writing and listening to music, and I’ve been diving into all my musical favourites, which for me means the great works of Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, and many highlights of Romantic and Modernist composers. I started making playlists of my absolute favourites, firstly as it made locating them easier, but then I remembered from my teaching days the idea from Wellbeing Theory (associated with Dr. Martin Seligman’s Positive Psychology) that musical playlists could be used to spread happiness and contentment in your life, rather than, say, merely entertainment. The concept of wellbeing is an often misunderstood one. When we hear the word ‘happy’, many of us think of rather simplistic, superficial perkiness, or the kind of forced jollity encouraged by American motivational speakers (or fast food chains). Seligman wanted to encourage genuine happiness in many domains; the term ‘wellbeing’ is more all-encompassing and, I think, involves a more middle-ground awareness not only of the gloriously pleasant and fun, but of the more slow-paced, profound contentment that can come from an awareness of the ordinary, the everyday or even the poignant or tragic. (An idea brought home by Pixar’s brilliant “Inside Out”, I might mention.)

So here is where my search began within the realm of music: I was seeking not just “fun toons” but something more therapeutic.

Popular music

Popular (non-classical) music, to me, is the music of society – it’s music for dancing to at parties or entertaining crowds at concerts. But we aren’t always in a social situation and social music without society can seem lonely or out of place. Furthermore, social music tends to be rather superficial because it must appeal to the tastes of a broad audience. The result is a certain sameness: pick your genre and that will usually indicate the mood; songs generally have the conventional verse-chorus-verse form with only slight variations on this. This music can get old quickly, suggesting pop music has a short shelf-life requiring constant novelty (who knew?). Plus much of the profundity of popular music comes from un-musical associations: through the verbal expression of the lyrics, or via nostalgia – ‘remember the first time I heard that song?’ Am I valuing this music or my own capacity to reminisce?

Western classical

Like Beethoven, with a blast of disapproval, I shifted from my popular playlists, and returned to my roots – in Western classical. Here there was more complexity: music reflecting great narratives, historical and philosophical developments, even experimental art. Here the mood could be fractious and ever-changing (Beethoven tends to interrupt conversation at parties), the formal structures diverse and unpredictable: yes, much of it is in sonata form but with longer duration, more diverse instrumentation, and complex musical techniques. I sought Classical works without too much doom-and-gloom as my goal was contentment not morose depression – so I focussed on works with a balance of moods and lots of interest – like Beethoven’s 9th: rousing melodies, contrasting tone colours, inventive variation and development, balanced form, a satisfying movement from dark to light…

And yet, even here, I began to have my own doubtful ruminations (in the lower strings). Even complex and artful developments become learned, predictable and stale over time. Even manageable variation in mood made listening difficult because you couldn’t experience satisfactory resolution unless you sat through the whole thing – and Beethoven’s 9th goes for over an hour. (A lot of Western Classical is essentially in a state of perpetual instability until the final resolving cadence…) And I loved those beautiful singable melodies yet I kept waking up in the night with Bach polyphony or Beethoven variations going around and around in my head. It seems Western Classical is just a more long-winded, complex, highbrow form of popular music, its epic masterpieces actually just a refined form of bombastic entertainment.

Most Western music is too ‘rational’

The problem, I think, has to do with discrete formal structures and ‘verbal’ phrasing. Western music is so very specific, and not only in terms of its notation systems. Each component of a piece of Western music is precisely positioned to produce ‘X’ effect – establishing a theme or varying it or resolving. This makes Western music almost like language, like someone speaking, because language is similarly made up of discrete parts arranged in a specific order. Consider a melody like ‘Greensleeves’ or ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’: the first phrase ends on a musical comma, like someone asking a question or starting a discussion. The next finishes the ‘sentence’ with the perfect cadence acting as a full stop. (Beethoven’s “Hunt” piano sonata no. 18 embarks on a whole flirtatious conversation!) I was seeking music that was meaningful throughout, not just when it had finished its ‘conversation’ (its often laborious ‘explanation’). Furthermore, it’s full of what I call ‘eventism’ – instead of music as a flow of pure experience, it becomes strictly linear with a beginning, middle and end like a narrative. This isn’t music for the everyday but for special occasions where the whole apparatus of a concert with a focussed audience has been assembled; it’s ‘chunky’ and inflexible, almost ‘commodified’.

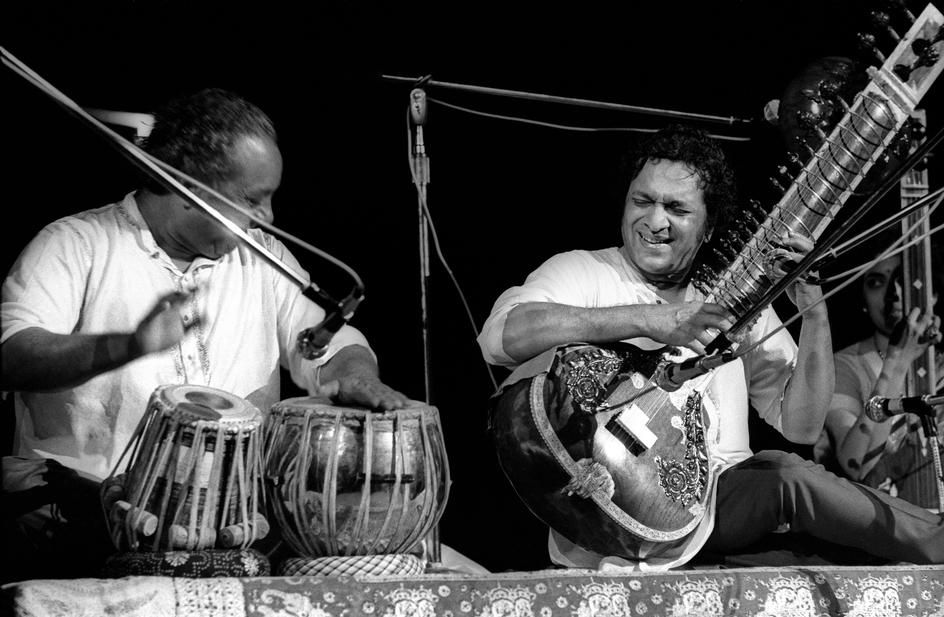

Indian Classical music

Then I remembered an odd experience that I had some 20 years ago. While studying mythology and religion, I thought I’d take a look at Indian Classical music: I did a quick Google search, watched a Youtube clip of Ravi Shankar playing at Woodstock, and spontaneously burst into tears. Odd that. Mythologist Joseph Campbell described Indian music’s powerful effect as deceptively emerging from the ordinary and everyday. You listen and it just sounds like musicians tuning up, then all of a sudden you notice that it has been this amazing music for some time, occasionally even the most exciting dance rhythms and all, and you didn’t even notice. It occurred to me now that it would be just like India, with its unique continuity of humankind’s ancient religious traditions (free from the corruptions of excessive literariness, dogmatic morality, defeatist eschatology, or secular rationality and individuality), to have discovered the healthiest type of music. Typical.

So what’s so good about it? Firstly, a majority of the music is improvised, which provides freedom and spontaneity, plus it makes no two performances identical so the music is hard to get tired of. However, improvisation can sound disjointed and rather structure-less, leading to the effect of aimless noise (even nihilism). This is usually remedied by frequent repetitions of set structures, such as effectively a kind of ‘chorus’ in between improvised variations by a performer – although this often returns us to the verse-chorus-verse structure of the popular song. Jazz, for example, also utilises standard chord structures (the famous ‘12-bar blues’) and consistently syncopated (‘swing’) rhythms. I find jazz to be either boring or too repetitive, plus its constant mood of ‘cool’ suggests this is music of society and fashion again. But in Indian Classical the method of providing structure to the improvisation is uncommonly brilliant. Enter the famous raga.

A raga is a strange combination between a collection of pitches (like a scale) and not so much a melody as melodic structures. This blurring of harmonic and melodic elements is a clue to its effectiveness as a loose improvisational structuring device (along with the rhythmic counterpart, the tala). The raga determines the scale of notes that the improviser uses, but also includes rules of melodic movement with many, for example, having a slightly different pattern of notes on the way up than on the way down. The performer begins most pieces with an alap, a slow-paced improvisation on the raga (that part that sounds like tuning up), often leading to a gat or bandish, an instrumental or vocal composition before more improvisation and a jhala, a fast-paced ending section where the rhythm overpowers the melody. Syncopation is prominent but not within the metre itself (like with jazz) – it’s not regular so it ebbs and flows rather than ‘swings’.

The instrumentation is intimate, spare and consistent, usually made up of no more than a melodic line, a drone, and percussion, usually a tabla (twin set of drums). The melodic line is performed by a vocalist or one of various plucked string instruments such as the sitar, sarod, or veena, or a reed instrument such as the bansuri (bamboo flute) or harmonium (a kind of accordion). The drone is a pedal note on the tonic (foundation note of the raga) usually played on the sitar-like tambura or tempura. The melodic line and the tabla don’t rhythmically coincide closely, contributing to the sense of flow, enhanced by the drone which pervades the performance with an other-worldly unity, famously symbolising Om, the sonic representation of the Divine essence of the universe and/or consciousness. (Figuratively, the drone is the ongoing foundation of the universe, while the raga and tala dance and play out particular expressions of species, environment, times, consciousness or other potentials.)

All of this results in hardly any discrete ‘sectionality’ or ‘eventism’. Both the melodic raga and the rhythmic tala are characterised not by restrictive structures but something like what is called in Western music ‘motivic’ development or ‘motivic cells’: small patterns of just a few notes (or rhythms) which recur and alternate but don’t often repeat precisely or with exact regularity. This ensures unity (since it is made up of restricted elements) while permitting irregular phrasing, retaining interest and avoiding ‘language effects’. The performer can also execute small glissandos or vibrata in the melodic line (vocally or by employing the pitch-wobble effects on the sitar), again eliminating discrete note partitions. Even the sectional boundaries between the formal structures like the alap and gat/bandish don’t sound discrete, organically merging into each other.

Most radical of all (for the Western listener) is the absence of harmonic progression – the one raga is the foundation of the whole piece, and there are no true chords at all. (This is like being stuck in, say, F major and never encountering a chord progression.) This would be monotonous except that without harmonisation (the pitched elements are mainly solo or in unison) the listener hears more a constant possibility of harmony rather than either an absence or presence. I realised that, in Western music, while harmony contributes to directionality and mood, it actually restricts meaning by slicing the music vertically into sections; much of Western music is ‘locked’ to the chord assigned to that particular metric unit to avoid discord thus limiting flexibility, motion, and interpretative possibilities, each moment thus having limited ‘meaning’. Harmony in Indian Classical is only implied by the sequential pitches in the raga as the notes only truly coincide with the tonic drone and with the sympathetic strings of an instrument like the sitar, if present. (Sympathetic strings are not struck directly by a performer but make a kind of resonant, sometimes slightly dissonant buzz as a result of the principle of harmonic vibration, like with tuning forks.) The effect blurs harmonic boundaries but in a highly organic way (considering the distortion is made by natural vibrations of harmonic likeness).

The overall effect of listening to Indian Classical is calming but not boring – subtle enough to be entertaining but not immediately thrilling as this would shatter the calm. Neither is it ever depressing or drab. Furthermore, it can be faded in and out at just about any point without greatly distorting its overall effect. On first listening, it resembles folk music, but with what sounds like a weak, meandering, unmemorable melodic line, but, ironically, the lack of a conventional melody with its discrete phrasing is where the majority of the interest and invention is located – no sleepless nights with annoying ‘earworms’ here. Indian Classical has some unfortunate associations with the hippie movement, and it does seem an appropriate accompaniment to free love and drug-taking with its free-flowing nature and its psychedelic drone, but careful listening suggests that you are actually only hearing the overlap between bohemian ideas and the more complex psychological depths of Indian religion, out of which this music emerged. This association needs to be seen through in the same way that appreciating organ music requires a conscious dissociation with staid Christian church services (or, similarly, rap with criminal activity).

The overall effect of Indian Classical is one of flowing calm, but with a sense of understated variation or suspended interest that I never really get tired of. I can listen to it anywhere at anytime and it both soothes and occupies one’s mind. (The ideal for me is Indian Classical with something similarly low-key to occupy me visually such as going on a walk around my neighbourhood or watching videos of motion such as Youtube videos of train journeys or drone footage.) The effect is fulfilling in a distinctly ordinary and human way.

More Wellbeing Music

My newfound appreciation for Indian Classical set me wondering what other types of music might be similarly therapeutic, if for no other reason than it is nice to mix it up sometimes. Here is what I discovered:

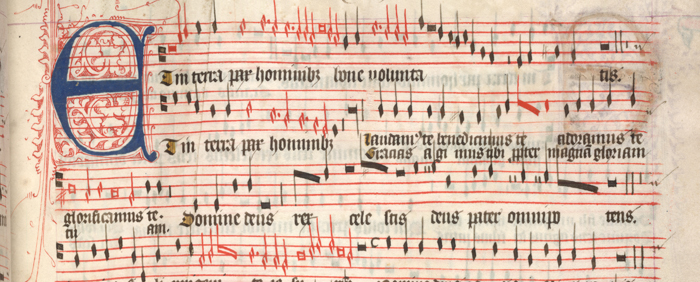

European medieval plainchant

Gregorian chant is of course unaccompanied vocal music sung in monophonic unison, without time signatures, built from non-diatonic modal scales, with melodies constructed in arch-like phrases which, significantly, are not expressive of specific emotions nor depict discrete images. This means that plainsong isn’t declamatory; it has no message to impart in a ‘verbal’ way except the pure sequence and sound of the tones themselves. While later European church music can sound pompous and moralistic through its depiction of Christ’s suffering, God’s blessings or pious outrage, medieval plainsong reflects the belief that the Latin text (itself mystically obscure) and its modal melodic lines were holy in themselves – much like Indian ragas. The development of the Notre Dame organum and discant styles of Leoninus and Perotinus through the 12th and 13th centuries largely maintain the sense of restful suspension in motion (Leoninus even employs a drone) often with just two voices (still no diatonic triads). Beyond into the 14th century and the Renaissance, I find the mood becomes too ‘secular’ with polyphony leading to harmonic ‘chunking’ and more prominent use of thirds adding more ‘mundane’ drama. Plainchant can sound monotonous though, but to break up a long session of Indian Classical, it can be quite refreshing, especially, for some reason, in the morning hours.

Western Classical ‘Impressionism’